August 10, 2012 | By Jamie Hopkins

High bidder for Baltimore County steel mill redevelops industrial sites, is partnering with a liquidator

By Jamie Smith Hopkins, The Baltimore Sun

10:53 PM EDT, August 10, 2012

Steel from Sparrows Point built the Golden Gate Bridge, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, hundreds of ships for World War II and livelihoods for tens of thousands of Baltimore-area families.

The story of the massive steel mill follows the arc of American manufacturing — rapid ascent, years of dominance, a generation of shrinking employment and decline. In the last dozen years, the mill has had five owners, two bankruptcies and many furloughs.

Last week came a stark warning that the final chapter in its 125-year history could be at hand. At a court-ordered auction Tuesday in New York, a redevelopment firm partnering with a liquidation company won the bidding for Sparrows Point.

“This was once the largest steelworks in the world,” said Deborah Rudacille, author of “Roots of Steel: Boom and Bust in an American Mill Town,” a workers’ history of Sparrows Point. “So the fact that it’s now being liquidated is hugely significant, not only for Baltimore but for the entire American steel industry.”

Some already are mourning. Others vowed to fight, to spend the next months searching for a company that wants to run the mill rather than dismantle it. Still others are fighting another battle — to avoid a repeat of the last bankruptcy’s aftermath, when a judge ruled that the company buying through the bankruptcy sale was not on the hook to clean up any pollutants left by its predecessor.

The $72 million bid for the mill — made by St. Louis-based Environmental Liability Transfer as part of a joint venture with Illinois-based Hilco Trading — is pocket change compared with the $810 million that Sparrows Point sold for in 2008. Steel analysts were perplexed.

Both Environmental Liability Transfer and Hilco declined to comment, and the deal isn’t final unless approved by a federal bankruptcy judge. A hearing is scheduled Wednesday in Wilmington, Del.

Approximately 2,000 men and women worked there until the mill was idled following the May bankruptcy of owner RG Steel. All anxiously await answers. What are the buyers’ plans? When will the benefits paid by RG Steel to the ranks of the laid off run out? How bad will the ripple effect prove?

The company said in an email to managers after the auction that Hilco “pledged not to destroy key steelmaking assets for 6 months while the unsecured creditors attempt to find an operator.” But beyond that, little is known.

“It’s such a mess,” said Dundalk resident Mike Hartnett, 56, who is the fourth generation of his family to work at the mill — his daughter is the fifth. “It’s going to be devastating to the community. When you consider the contractors, the vendors, the local businesses that are going to be impacted by it, it goes very, very deep.”

Until recent weeks, Sparrows Point was one of the largest private employers in Baltimore County. But once it was the state’s largest, with more than 30,000 employees during steel’s post-World War II heyday.

The operation itself dates back to 1887, when the Pennsylvania Steel Co. bought up farmland to build a modern steelworks. Sparrows Point’s first pig iron was produced in the new blast furnaces two years later.

Bethlehem Steel, the mill’s longest owner, snapped the complex up in 1916. The company built almost 500 Liberty and Victory ships near Sparrows Point during World War II — it ran shipyards as well as the mill — and supplied steel for major capital-improvement projects.

Besides the Golden Gate and Chesapeake Bay bridges, Sparrows Point steel was shipped out to build Boston’s Third Harbor Tunnel (now the Ted Williams Tunnel) in the ’90s.

For decades Bethlehem Steel ran a company town for employees and their families that included, by Elmer Hall’s count, seven churches, four schools, a bowling alley, a movie theater and multiple stores and restaurants. “Not to mention the 5,000 residents,” said Hall, who grew up there.

The town was torn down in the early 1970s to make way for the massive “L” blast furnace that’s still in use today. Or was, until the bankruptcy.

Now 70 and living in Parkville, Hall organized a reunion of former company-town residents — Aug. 18 from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. at North Point State Park — to coincide with Sparrows Point’s 125th anniversary. He didn’t expect that it also might be the mill’s final year, or that the book he’s writing about the mill’s history could reach from start to finish.

“This could be it, as far as the final footnote,” said Hall, whose parents worked at the mill and who worked there himself before he became a teacher.

Joe Rosel, president of United Steelworkers Local 9477 in Sparrows Point, isn’t ready to write the steel mill’s obituary. Like many at the mill, he followed relatives to work there. He wants younger residents of the region to have a shot at the good-paying jobs with benefits that the mill provided.

“I don’t want this to go down this way, I can tell you that,” he said the morning after the auction. “My members are fighters and I’m a fighter, and we haven’t given up.”

His plan is to use the six-month grace period promised by Hilco to find another buyer — an industry buyer, someone with the ability to run Sparrows Point and the interest in doing so. While no potential operators bid on the plant, that may reflect the speedy auction process more than a lack of interest. Or so Rosel and others hope.

It’s a last-chance effort. County Executive Kevin Kamenetz said on Wednesday that he’ll work with the union to try to make it happen. A spokeswoman for Gov. Martin O’Malley said he would also offer his support.

Government officials already are fielding ideas. Niall H. O’Malley, managing director of Blue Point Investment Management, a Towson advisory firm, and no relation to the governor, pitched one to a state economic development commission on Thursday. He suggested reducing Maryland’s corporate income tax rate in a big way on profits generated from investments in new manufacturing facilities for 10 years.

He said such a move would show that officials are serious about wanting Sparrows Point and other manufacturers to thrive, and they wouldn’t have to offer incentives upfront to do it.

“It does sound like there is a window of opportunity,” O’Malley said of the steel mill. “This is a huge legacy manufacturer and one that should not be ignored.”

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation thinks another issue shouldn’t be ignored — steelmaking toxins on the site and in the water. The 2,400-acre complex sits against the Patapsco River, near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, as well as Bear Creek, Jones Creek and Old Road Bay.

Among other problems, the chemical benzene, a known carcinogen, has been found in groundwater in the complex’s Coke Point peninsula “at levels thousands of times” above what the Environmental Protection Agency determined is safe, said Jon Mueller, the foundation’s vice president for litigation.

A 1997 consent decree between Bethlehem Steel, the EPA and the state laid out requirements for the company to find and remediate contamination it had caused. Then came Beth Steel’s bankruptcy. In 2011, a federal judge ruled that the terms of the 2003 bankruptcy sale meant that the new owner couldn’t be held liable for toxins created before that point.

The consent decree still does require any owner to identify contamination in the water nearby and to fix more recent problems, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation said. The nonprofit is worried that the second bankruptcy will throw those efforts into limbo — particularly with a buyer specializing in liquidation — unless it is made clear in any sale order that the responsibilities don’t end with RG Steel. The foundation as well as both state and federal environmental regulators have filed objections in the case.

“We represent a number of individuals who … live nearby and who fish or used to fish right there in Bear Creek or used to swim in Bear Creek and are afraid to do so because they don’t really know what’s in the water,” Mueller said. “The uncertainty is what continues to haunt people.”

Residents near Sparrows Point filed a lawsuit Thursday against RG Steel and a cement maker there, seeking damages for alleged risks to their health and contamination of their property.

If the mill is scrapped, its components could spread to the four winds, some intact, some melted down. Rudacille, whose father, grandfathers and other relatives worked at the mill or the shipyard, sees a sad sort of full circle to that possible end.

Sparrows Point was built in part using the remains of the Ashland Iron Works in Cockeysville, she said.

“Now they’re probably going to break it down and recreate it somewhere else,” she said.

Baltimore Sun researcher Paul McCardell contributed to this article.

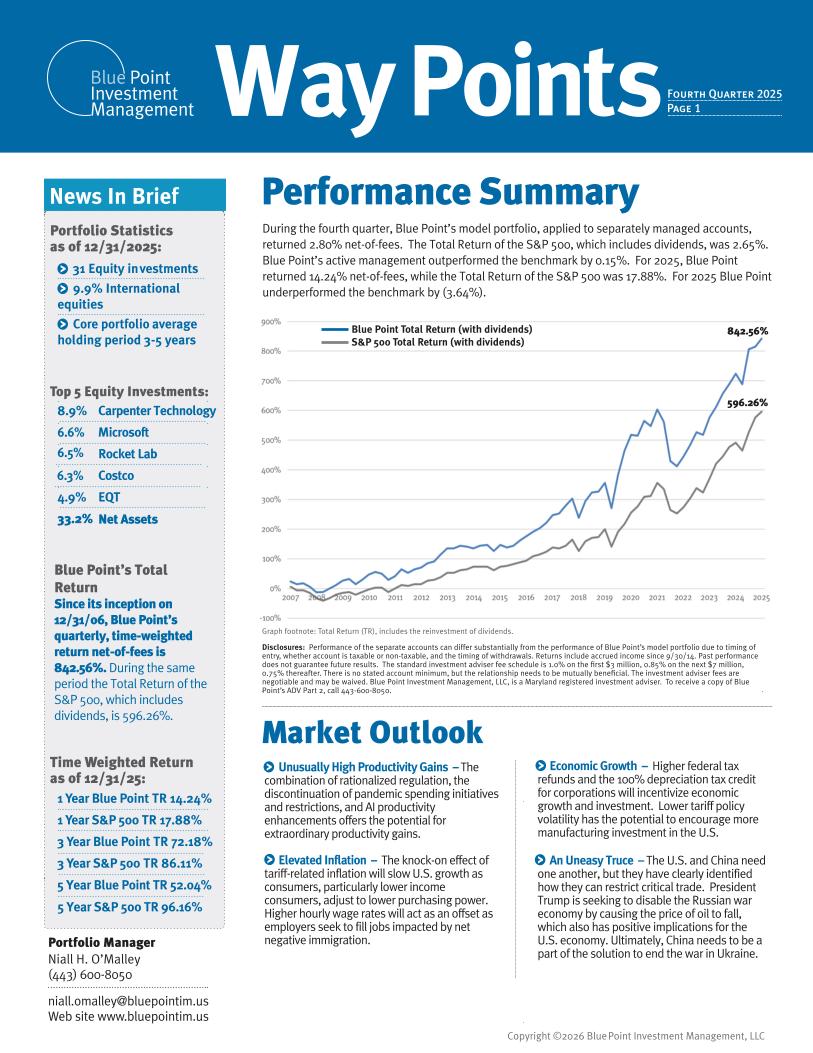

Back to Previous