April 23, 2010 | By Scott Dance

The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed above 11,000 for the first time in more than a year and a half April 12 — marking a return to a height not seen since a tumultuous September 2008 that shook Baltimore and Wall Street. But can the same be said for local stocks?

Many of them are still well below early 2008 levels. Shares of Constellation Energy Group Inc., which was pulled to the brink of bankruptcy that fall, are worth half of what they were before the downward spiral. The same can be said for Legg Mason Inc. or FTI Consulting Inc. OtThe Dow Jones Industrial Average closed above 11,000 for the first time in more than a year and a half April 12 — marking a return to a height not seen since a tumultuous September 2008 that shook Baltimore and Wall Street. But can the same be said for local stocks?

Many of them are still well below early 2008 levels. Shares of Constellation Energy Group Inc., which was pulled to the brink of bankruptcy that fall, are worth half of what they were before the downward spiral. The same can be said for Legg Mason Inc. or FTI Consulting Inc. Others, like McCormick & Co., W.R. Grace & Co. and T. Rowe Price Group Inc., are at or above pre-recession prices.

Stocks’ prices relative to previous peaks depend largely on how businesses — and their earnings, in particular — have been affected by the recession. Some, like Constellation, were forced to shed risky and expensive business activity and now face a perception of lower potential for profits. Others, such as Columbia-based real estate investment trust Corporate Office Properties Trust, have come out ahead as they have been able to outmaneuver competitors felled by the economy.

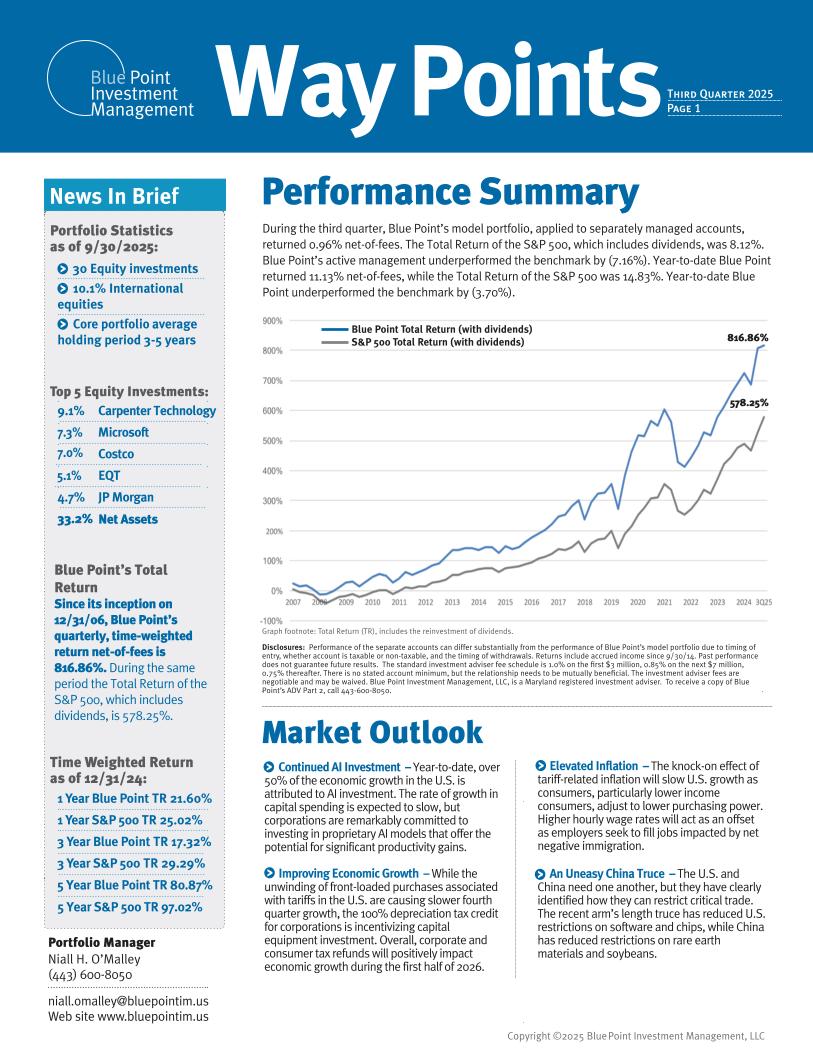

“You had systemic change in 2008 with the financial crisis,” said Niall O’Malley, managing director of Baltimore investment adviser Blue Point Investment Management LLC. “These large corporations are challenged because what they were developing themselves for in their market has shifted.”

How companies manage those new environments will determine where share prices go from here, stock market observers said. But what they can do also depends on how Washington decides to regulate Wall Street going forward.

Constellation was perhaps the preeminent local face of the rapid economic deterioration of September 2008. Linked to Lehman Bros., then headed toward bankruptcy itself, the energy company faced a dangerous cash crunch in its commodities trading business. Its stock price had been between $70 and $80 per share that summer, but as the Dow plunged below 10,000 for the first time since 2004, Constellation’s shares fell as low as $25 in October 2008.

After a flurry of negotiations with French utility EDF Group and billionaire Warren Buffett, the company nearly consummated a deal to be bought by Buffett’s Mid-American Energy for $4.7 billion. That union was nixed in December 2008 in favor of a $4.5 billion sale of half of Constellation’s nuclear assets to EDF.

Since then, the company has moved ahead with a rebuilding plan, but its stock hasn’t matched previous levels. And it may not in the future. But that is not a surprise, said Angie Storozynski, an analyst with Macquarie Capital, who covers energy companies.

“They don’t have 50 percent of their nuclear plants, and they don’t have a trading business,” she said. “That has to be adjusted.”

Storozynski is expecting a $41 per share price within the next year; shares closed at $37.47 April 21. She pointed to the company’s 36 percent spike in share price over 2009 as a sign of strength over others in the energy industry.

Jack Thayer, Constellation’s chief financial officer, said in an interview that for his company and others impacted by the financial crisis, that is to be expected. To right itself for the future, Constellation has focused on strengthening its business generating and selling power. It sold off its coal and natural gas trading business units to shed risk and reduce its need for large amounts of cash.

“Anytime you divest businesses that are performing, clearly you’re choosing to focus your strategy, and you reduce your prospective earnings outlook,” Thayer said. But he said he expects the growth in the generation business to make up for the profits from the lost business units.

Other firms have had to make similar adjustments that make them a gamble for investors. Banks, for example, are under increasing scrutiny to limit overdraft fees on consumers’ checking accounts, said Jeff Rottinghaus, portfolio manager of the U.S. Large-Cap Core Fund at T. Rowe Price. Bank of America, for example, Greater Baltimore’s largest by market share, plans to end overdraft charges this summer, prompted by federal regulation. Its stock closed at $18.28 April 21, down from a peak of $37.48 in September 2008.

Rottinghaus predicts that instead, banks will look to new fees on opening checking accounts or on loan products. Whether that will allow them to command the same amount of earnings remains to be seen.

“Businesses will always adapt and always try and find a way to recover any lost revenue,” he said. But with the muddled picture for future financial regulation, the companies “can’t speak with a tremendous amount of certainty as to what their business model is going to look like. It’s difficult to model what their potential earnings power could be,” Rottinghaus said.

Still, other companies have been required to take new tactics because of the economy and ended up ahead. Spice maker McCormick has enjoyed profits stemming from more families opting for cheaper, home-cooked meals. And Corporate Office Properties Trust has rode the surge in opportunity coming through federal government and military spending.

hers, like McCormick & Co., W.R. Grace & Co. and T. Rowe Price Group Inc., are at or above pre-recession prices.

Stocks’ prices relative to previous peaks depend largely on how businesses — and their earnings, in particular — have been affected by the recession. Some, like Constellation, were forced to shed risky and expensive business activity and now face a perception of lower potential for profits. Others, such as Columbia-based real estate investment trust Corporate Office Properties Trust, have come out ahead as they have been able to outmaneuver competitors felled by the economy.

“You had systemic change in 2008 with the financial crisis,” said Niall O’Malley, managing director of Baltimore investment adviser Blue Point Investment Management LLC. “These large corporations are challenged because what they were developing themselves for in their market has shifted.”

How companies manage those new environments will determine where share prices go from here, stock market observers said. But what they can do also depends on how Washington decides to regulate Wall Street going forward.

Constellation was perhaps the preeminent local face of the rapid economic deterioration of September 2008. Linked to Lehman Bros., then headed toward bankruptcy itself, the energy company faced a dangerous cash crunch in its commodities trading business. Its stock price had been between $70 and $80 per share that summer, but as the Dow plunged below 10,000 for the first time since 2004, Constellation’s shares fell as low as $25 in October 2008.

After a flurry of negotiations with French utility EDF Group and billionaire Warren Buffett, the company nearly consummated a deal to be bought by Buffett’s Mid-American Energy for $4.7 billion. That union was nixed in December 2008 in favor of a $4.5 billion sale of half of Constellation’s nuclear assets to EDF.

Since then, the company has moved ahead with a rebuilding plan, but its stock hasn’t matched previous levels. And it may not in the future. But that is not a surprise, said Angie Storozynski, an analyst with Macquarie Capital, who covers energy companies.

“They don’t have 50 percent of their nuclear plants, and they don’t have a trading business,” she said. “That has to be adjusted.”

Storozynski is expecting a $41 per share price within the next year; shares closed at $37.47 April 21. She pointed to the company’s 36 percent spike in share price over 2009 as a sign of strength over others in the energy industry.

Jack Thayer, Constellation’s chief financial officer, said in an interview that for his company and others impacted by the financial crisis, that is to be expected. To right itself for the future, Constellation has focused on strengthening its business generating and selling power. It sold off its coal and natural gas trading business units to shed risk and reduce its need for large amounts of cash.

“Anytime you divest businesses that are performing, clearly you’re choosing to focus your strategy, and you reduce your prospective earnings outlook,” Thayer said. But he said he expects the growth in the generation business to make up for the profits from the lost business units.

Other firms have had to make similar adjustments that make them a gamble for investors. Banks, for example, are under increasing scrutiny to limit overdraft fees on consumers’ checking accounts, said Jeff Rottinghaus, portfolio manager of the U.S. Large-Cap Core Fund at T. Rowe Price. Bank of America, for example, Greater Baltimore’s largest by market share, plans to end overdraft charges this summer, prompted by federal regulation. Its stock closed at $18.28 April 21, down from a peak of $37.48 in September 2008.

Rottinghaus predicts that instead, banks will look to new fees on opening checking accounts or on loan products. Whether that will allow them to command the same amount of earnings remains to be seen.

“Businesses will always adapt and always try and find a way to recover any lost revenue,” he said. But with the muddled picture for future financial regulation, the companies “can’t speak with a tremendous amount of certainty as to what their business model is going to look like. It’s difficult to model what their potential earnings power could be,” Rottinghaus said.

Still, other companies have been required to take new tactics because of the economy and ended up ahead. Spice maker McCormick has enjoyed profits stemming from more families opting for cheaper, home-cooked meals. And Corporate Office Properties Trust has rode the surge in opportunity coming through federal government and military spending.

Visit Link Back to Previous